Meri Radinibaravi | 10 April, 2023, 8:30 pm

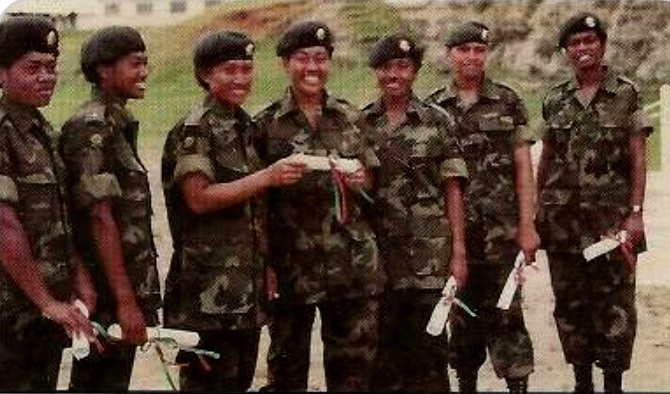

The seven female officers who were commissioned in December, 1988. Picture: SUPPLIED

Part 1

The history of a national military force in Fiji goes way back to 1920 before independence. But one thing was certain then, the army was no place for women. Women worked in garment factories, were nurses, teachers, policewomen (the first joined in 1970), but most stayed home.

The concept “a woman’s place is in the kitchen” was widely embraced in Fiji and around the Pacific and women have always been considered as “soft”. This, in my opinion, was probably one of the reasons women were never recruited into the army.

It wasn’t until the incumbent Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka became the Commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) in 1987 that he allowed the first batch of Fijian women to enter the RFMF in 1988.

Colonel Silipa Raradoka Druavesi Vananalagi was one of 41 woman who decided to break the stigma in 1988 by enlisting in the RFMF.

Out of the 41 women, only seven were commissioned as officers.

Originally from Taci Village, Noco in Rewa, Ms Vananalagi grew up in a family that was predominantly male to parents who also featured in Fiji’s political scene in the mid to late 1900s.

Her father, the late Atunaisa Bani Druavesi, was a banker by profession, but later joined the Soqosoqo ni Vakavulewa ni Taukei (SVT) political party.

Her mother Ema Druavesi was a career lab technician before joining the Fiji Trades Union Congress (FTUC) and later the Fiji Labour Party (FLP) for the 1987 election.

Ms Vananalagi was a student at the prominent Adi Cakobau School (ACS) when the 1987 coup happened.

That, she said, was the first time she “started seeing the green uniform”. “I was still in school in 1987 when the FLP won the elections of ‘87 and then we were told that school was closed because of the coup,” Ms Vananalagi reminisced.

“One of those experiences was mum arrested for a while, and I had to collect stuff from home and take it to her while she was still in CPS (Central Police Station).

“(She) was telling me what to do, what not to do, this is what to bring and all that and being a high school student at the time and facing that crowd of people in uniform, both police and military with guns — it was something challenging, but I had to do what she tasked me to do.

“That was when I started seeing the green uniform.”

When an advertisement appeared in the dailies for women to join the RFMF, Ms Vananalagi applied. That did not go down well with her mother. She had wanted Ms Vananalagi to follow her father’s footsteps in becoming a banker.

“I saw the advertisement on the local newspapers, and I decided to apply and interestingly, my mother was against me applying for the military.

“I was one of the fortunate females that was allowed to attend the women’s WORSBY (Women Officers Regular Selection Board).

“They called it the women’s WORSBY then, where they selected a few women to go through a four-day training program through which they did assessments to see whether you’re fit to be a future officer of the RFMF.

“They see all your calibres in leadership, team bonding and everything including social activities. “On February 5, 1988, we were at the Force Training Group (FTG) for our first day of recruit training.”

Ms Vananalagi said the challenges began as early as day one. “When we started, there was no boundaries between men and women.

“So, there’s this fitness test that we do, depending on the age group, and we women at that time, we had to run the same time with men and it was like running 2.4km in nine minutes.

“And after doing the run, you do the exercises.

“The sit ups, the press ups, and we actually did chin ups during that time and we had to do seven until I think it was in early ‘89 or mid ‘89 when they phased out chin ups for women but we did that during our cadet time and when we graduated.

“We thought we couldn’t do it, but we did it and like we were just challenging men at the same time.”

Ms Vananalagi said there were times when the 41 women were ridiculed for not being able to complete a certain task that men were able to complete. They were also made fun off for being the only women in the army.

This included being called names by army wives who lived in the barracks with their husbands and families.

“To be seen wearing the green uniform and holding guns, you would hear all sorts of comments, it was endless. “But I think the comments that we got during those days, that really built us personally, especially for me and my character, to what I am today.

“It has made me strong; I accept all sorts of criticism, I take on the constructive ones and I just disregard the nonsense one and just move on.”

Another challenge the women faced was the lack of privacy as there were no “women only” facilities because the army at that time, was not structured to include female soldiers. So, when the first batch of women entered the army, they had to use the same facility as the men.

“There was no proper infrastructure in place for women only, like sometimes we just wanted our own privacy and that we didn’t have that. We didn’t get that opportunity.

“If you go into a bathroom and if somebody comes along you had to say “ei au jiko qo i loma” (Hey, I’m inside here) and then you know the boys would know that there’s someone in there.

“Sometimes it was fun when you think of it because we used to rush to see who goes in first.”

But the main challenge that these women faced was the ranking system.

According to Ms Vananalagi, when they entered the force there was a policy in place that limited their promotion.

“When we entered in 1988, we had this policy that said that women could only go up to the rank of captain and once you get married, you have to resign and reapply to the force after you’ve given birth.

“If there’s a vacancy, then they take you back. “Nobody was there to guide us; we didn’t have proper mentors.

“It was lucky if you were in a unit where you will be told this is right and this is wrong.

“Otherwise, you will just go with the flow.

“There were courses, like as an officer you start off with doing Junior Staff Officers (JSO) course and then you go to grade three, grade two, then if you’re fortunate to do joint warfare, well and good.

“Otherwise, you’d do Staff College then to Defence College.

“But for us, we were told that we could only do JSO course, that was it.

“So, I think for us, as a team, we took on the challenge and we really tried to make our way to be recognised in the military, especially since it’s a maledominated organisation. “One wrong thing you do, they really pick it out fast and they will always talk about it every now and then.

“But for us, it was like a learning phase.”